2022 Listening Tour

In April 2022, Dr. Ray Dorsey spent a week driving around New York to hear from communities hit by pollution. In May, he went to Pennsylvania, and in June he traveled to Arizona. Though the spills may have occurred decades ago, the impacts live on. Below, Dr. Dorsey shares journal entries from each day.

Are you part of a community that has been impacted by contamination or chemical dumping? We would love to hear from you. Email info@endingpd.org.

“Think”

The word “THINK” emblazons an old IBM building in Endicott, N.Y.

In 1911, a company that would become known as IBM was born in Endicott, NY. At its peak, the computing giant would employ 14,000 people locally, more than the city’s current population.

The company had its own country club, and a bridge over the Susquehanna River was named for longtime IBM chairman and CEO, Thomas Watson. The city, located at the state’s southern border with Pennsylvania, had been previously known for manufacturing shoes. Now it was a global computer capital.

However, the joy, prosperity, and pride IBM brought to the city began to decline in approximately 1980 when a widely used chemical in the electronics industry called trichloroethylene, or TCE, was found in the city’s water. Two decades later, the dangerous chemical was found to evaporate from contaminated soil and groundwater and enter people’s homes, work places, and houses of worship. Individuals and their families were breathing in the toxic fumes and did not even know.

The story of Endicott’s pollution was featured in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and in medical literature. TCE is known to cause cancer and is linked to heart defects to children born in the area. It is also associated with a 500% increased risk of Parkinson’s disease.

However, like smoking and lung cancer, there is a lag between exposure to the toxin and the development of Parkinson’s disease. A 2012 study evaluated twins who were exposed to the chemical and found a 10-to-40 year lag between when individuals worked with the chemical and the ultimate diagnosis of Parkinson’s, which is known to take years to unfold. Decades later, the effects of TCE on Parkinson’s in this community and thousands of others could still be coming to the surface.

During the height of its use in the 1970s, more than two pounds of TCE were produced for every American. Up to 10 million people in this country worked with the chemical that was used in everything from decaffeinating coffee to degreasing machine parts to dry cleaning clothes. Today, the State of Michigan alone has thousands of contaminated sites. I live near one fifteen minutes from my house in suburban Rochester, NY. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has proposed banning the chemical but has yet to act. Global use of TCE continues to rise.

Yesterday, I was slated to attend a Rock Steady Boxing class with local residents with Parkinson’s disease. However, a spring snow storm left 50,000 people in the southern part of the state without power and cancelled the class. Today, I am slated to attend another class and visit another community affected by TCE in upstate New York.

IBM left Endicott in 2002. Many of its buildings are now in decay. However, one beautiful brick one with white pillars from 1933 remains. Engraved at the top is an admonition to “THINK”. Hopefully, this listening tour will help us all to think about what is fueling the rise of the world’s fastest growing brain disease, and what we can do to end it.

~Ray Dorsey, MD

“A Wonderful Place”

Toxic waste from nearby industrial giants was dumped into a hilltop landfill overlooking a pristine lake just outside the village.

For years, a local businessman trucked in toxic waste from nearby industrial giants into the idyllic town of Nassau, NY. Tankers dumped the chemicals into a hilltop landfill overlooking a pristine lake just outside the village. Initially, in the 1950s and 1960s, this activity went largely unnoticed. But according to local lore, that changed when teenage boys began developing sores on their skin after swimming in Nassau Lake. The boys were not the only ones affected. Cattle died, fish were poisoned, and uncontrolled fires blazed.

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation estimated that 46,000 tons of chemicals – double what was found at the notorious Love Canal – were disposed of at the site. The lake is fed by streams and other water sources that were contaminated by the landfill. Among these chemicals was the industrial solvent, trichloroethylene or TCE. In 1968, the State of New York ordered the landfill operator to stop dumping and to clean the site. Later, a second toxic Superfund site was found contaminated with TCE and other chemicals in town. This one was found in a residential area right next door to the businessman’s own home.

Just as in Endicott, NY, health concerns began to emerge from local residents. Whispers of cancer, common and rare, cropped up in many households living near the lake. Most were drinking, cooking, and bathing in water from private wells that were subject to contamination from the polluted landfill. Unlike city or municipal water, these wells are not regulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act and are infrequently tested.

This map chronicles clusters of cancer in the community. Red pins mark human cases, and yellow pins indicate animals.

By the 1990s, the community began surveying its residents and mapping clusters of cancer in red pins on a map. Fred McCagg’s family was one of those affected. “Everyone in my family had cancer,” said McCagg, the highway superintendent.

Among those affected included his only daughter who was diagnosed with a rare bone cancer, called Ewing’s sarcoma, which has been reported in other TCE-contaminated sites. At age 14, his daughter developed back pain and found a tumor in her rib. Despite aggressive therapy, she died before graduating high school at age 17.

In addition to causing cancer, TCE is associated with a 500% increased risk of Parkinson’s disease. Melody Howarth and her family also used to live near the Nassau Lake, previously used for fishing, water skiing, and recreation by locals. In 2014, the artist, avid swimmer, and town historian noticed a tremor in her jaw and her right hand. She was 56. She is not alone. Almost everyone in the town of 5,000 — from a local pastor to a long-time pharmacist — has heard of high rates of brain diseases in the community.

Clean-up efforts in Nassau have long begun. Water is pumped out of underground aquifers and toxins removed. Monitoring wells spring up from the ground all around the polluted sites. The feeling, according to one local resident, however, is that “millions of dollars have been spent on band aids.” The source of the contamination remains.

Asked what she would want people to know about Nassau, Howarth is quick to respond, saying that Nassau is “a wonderful community with loving families who have suffered needlessly.”

~Ray Dorsey, MD

“A High Price to Pay”

John Jay High School in East Fishkill, NY, has long prided itself on the academic development of its students. Today, the school has a Science Olympiad team, competitions for future business leaders, a forensics class, and a STEM program supported by IBM scientists. The close relationship between the school and the computer electronics company is not surprising. They are neighbors.

For decades John Jay High School sat between the East and West Complexes of a 600-acre IBM campus. The East Complex was used for manufacturing semiconductor and electronic computing equipment; the West Complex housed research and development.

“All Visitors and Workers Must See the Medic at Southside Entrance Before Entering Site” reads the sign outside IBM’s former West campus.

In the late 1970s, the soil and groundwater on the East Complex was found to be contaminated with trichloroethylene (TCE) and perchloroethylene (PCE). In 2005, IBM sold the West Complex to a real estate development company. Today, the construction site there posts a unique sign.

The toxic chemicals were widely used in the computer electronics industry and are found in more than half of Superfund sites throughout the country. Silicon Valley alone is home to more than a dozen.

These chemicals can contaminate nearby sites in at least three ways. The first is the industrial release of the toxins into the air. The second is through contamination of the underlying groundwater which can be used for drinking, cooking, and bathing. The third is via vapor intrusion in which the volatile chemicals evaporate from polluted groundwater and soil and enter homes, workplaces, and schools, often undetected. In 1981, the well at John Jay High School was found to have “slight contamination” even after installation of a water filtration system following the discovery of the pollution at IBM. Schools in California and North Carolina have had vapor intrusion.

The health consequences of attending or working at a school adjacent to a contaminated site are hard to discern, especially when other polluted sites are located nearby. One graduate of John Jay High School would like to know. At age 37, at the pinnacle of his career and immersing himself in each moment with his vibrant family, he developed his first symptom of Parkinson’s disease. He is a product of the community. His father was an engineer at IBM. His first home was located less than a mile from a Superfund site contaminated with TCE and PCE. His second was a similar distance from another TCE toxic Superfund site where a metal manufacturing company operated. He attended John Jay High School, which gave him the academic foundation to become a future physician, a profession that he can no longer practice. Along with many others in the community, he is concerned about the large number of individuals he knows who have had or died from cancer, many at disturbingly young ages.

The human toll of these polluted sites is never adequately reflected in any legal settlements or clean ups, even in the best of circumstances. Instead, we subsidize these toxic actions with the health of our neighbors, classmates, friends, siblings, parents, spouses, children, and selves.

~Ray Dorsey, MD

“What We Don’t See”

Following the environmental tragedies of the Love Canal near Niagara Falls and the Valley of the Drums near Louisville, KY, Congress enacted a law in 1980 that came to be known as Superfund. For the first time, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) could (1) clean up contaminated sites and (2) force responsible parties to pay the cost if they did not do so themselves. Today, there are over 1,300 such toxic sites in the country. Over the past three days, I visited five.

The word Superfund strikes fear into many. Images of danger signs with skull and crossbones, barbed wire fences, hazmat suits, dead birds, and toxic sludge come to mind. But none of the ones I visited look like that.

They are in ponds yards away from where children bike and live (Nassau, NY), near strip malls (Hopewell Junction, NY), under suburban neighborhoods (East Fishkill, NY), and below city buildings (Endicott, NY). There are no signs, no warnings, few obstacles.

Monitoring wells to assess the underlying contaminated water dot fields. Vapor remediation systems are found on several homes and buildings. But many have no protection. Some private wells are capped. Dozens of homes have their water now provided by municipalities, but some still drink, bathe, and cook with polluted water. At home in Rochester, NY, I drive past multiple contaminated sites weekly, if not daily.

We have permitted the above to become normal. We have allowed ourselves to believe that children developing leukemia is just a chance occurrence. We accept that one in eight women will have breast cancer. We think that Parkinson’s disease is a natural consequence of aging. We see Alzheimer’s as inevitable. All are lies. They are fictions that we, even in medicine, perpetuate, if not promote.

Monitoring wells like these dot the landscape.

There are reasons why Parkinson’s is the world’s fastest growing brain disease. The reasons are all around us. Toxic pesticides on farms, solvent-contaminated groundwater, indoor air pollution, and smog. The faster that we say that these are not acceptable, the quicker we raise our expectations, the sooner our suffering will end.

~Ray Dorsey, MD

“A Start”

After two years lost to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 28th annual Parkinson’s Unity Walk was held Saturday morning. The walk, organized by Carol Walton and her outstanding team, attracted thousands from all over the country and the world to the Naumburg Bandshell in Central Park.

Among the exhibitors at the walk, which raises research funds for four leading Parkinson’s foundations, was the PD Avengers.

Larry Gifford, founder and leader of the PD Avengers, has organized thousands of people with Parkinson’s across the globe.

The global grassroots organization is led by Larry Gifford, Soania Mathur, and Tim Hague, and now has over 5,000 members from 80 countries and 100 partner organizations. Supported by two creative and generous firms, Franklyn and All Good Things, the Avengers released a new public awareness campaign focused on a “spark” that will ignite a new wave of activism for the Parkinson’s community. This campaign takes its direction from those who know the disease most intimately – individuals with Parkinson’s.

Saturday was also the last day of my statewide Parkinson’s listening tour. Over five days and five hundred miles, strangers shared their homes, communities, and life stories with a tall neurologist from Rochester. I learned how pollution in communities are contributing to breast, brain, and prostate cancer and to Parkinson’s disease. Some individuals are faring well; some are not. Some are no longer with us, and many more remain at risk.

Over the journey, I have been inspired by the commitment of individuals to their neighbors like Melody Howarth in Nassau and heartened by the activism of people who seek justice like Debra Hall in Hopewell Junction. However, all of this is just the start. We will need more, much more to end the world’s fastest growing brain disease.

Tens of thousands from around the world are going to have to walk, march, and fight. Organizations like the PD Avengers need ten times more members and partners. These partners can come from media outlets, public relations, life sciences, engineering firms, fellow disease associations, youth groups, marketing, philanthropy, and public servants. If you can provide time, energy, or support of any kind, join the PD Avengers today. It is free, takes 30 seconds, and can change the course of the disease for this and future generations. Simply go to www.PDavengers.com.

The starting line at the 2022 Parkinson’s Unity Walk, the first after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, I need to listen and learn more. The clues to ending Parkinson’s disease are all around us. I would love to hear your stories so we can complete the puzzle. Email me at info@endingPD.org, and let’s finish Parkinson’s disease.

~Ray Dorsey, MD

“A Long Way to Go”

Elizabethtown is full of serene views like this one.

On a majestic spring evening in central Pennsylvania, I visited another Superfund site contaminated with the toxic chemical trichloroethylene (TCE). Along the farm fields in Elizabethtown, a waste disposal company and other “potentially responsible parties” polluted a landfill with TCE, manganese, and other chemicals (see map). The groundwater was contaminated, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identified “unacceptable risks due to the potential exposure of future well water users to contaminated groundwater through ingestion, [skin] contact and inhalation of vapors while showering.”

The site is fenced off, but like the sites I visited in New York state, there is little else to indicate the dangerous contamination that occurred there. In 1989, the EPA listed it as a Superfund site. Thirty-three years later, the site remains on that list.

Almost no community, no matter how rural or urban, populated or sparse, modern or dilapidated, is free from the wraths of this cancer-causing chemical. Yet despite its widespread use — more than two pounds were produced per American in 1970 — TCE’s effects on the rise of Parkinson’s are largely ignored.

A local water tower stands behind a fence.

Map of Elizabethtown Landfill Superfund Site. Note the proximity of the site to homes in the area.

I came to Pennsylvania from Miami, FL, where the Pan American Society of the Movement Disorder Society held its first in-person meeting since the COVID pandemic struck. There, new treatments for Parkinson’s were discussed, surgical approaches evaluated, and care models debated. But not a word was spoken about preventing Parkinson’s. In fact, more was discussed about preventing a purely genetic disorder, Huntington disease, than a largely man-made one, Parkinson’s. Almost the entire system from funders to pharmaceutical firms to researchers to clinicians have bought into a flawed notion that the best (only?) approach to Parkinson’s is better treatment. That has been the approach for the last 20 years, and we have precious little to show for it.

Prevention will spare future generations Parkinson’s and may help those who already have it. While no studies (to my knowledge) have assessed the effect of exposure of TCE or pesticides to those already with the disease, studies of air pollution, another likely contributor to Parkinson’s, are not re-assuring. A 2017 study in Korea found that short-term increases in air pollution were associated with aggravation of Parkinson’s disease. Three years later, a U.S. study found that increased air pollution “is significantly associated with an increased hazard of first hospital admission with Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.”

Clean air, water, and food are important for all of us. If we want to change the course of Parkinson’s, cancer, and Alzheimer’s, however, we are going to need to expand our focus beyond better treatments to address the underlying causes of these diseases.

~Ray Dorsey, MD

“IN HOT WATER”

The sun beats down in Phoenix, Arizona, where mountains encircle a beige city that hums under scorching triple-digit heat. But the true dangers lie beneath the surface.

Like in New York and Pennsylvania, Arizona is another state still paying the costs of the past. Through the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, companies soaked industrial chemicals into the ground. Today, Phoenix is home to one of the largest swathes of contaminated groundwater in the country, sprawling over 15 miles wide. The state has spent over $7 million on cleaning up the site since 1999, removing 13,000 pounds of contaminants, 3,100 tons of soil, and treating 118 million gallons of groundwater.

The sun rises over the city of Phoenix.

Throughout this process, though, some pollution isn’t erased – just transformed. Pollutants like trichloroethylene, perchloroethylene, and chromium can move from the groundwater into the air, consumed by the neighbors, shop owners, kids and communities.

Water treatment systems remove chemicals from some of the most contaminated water.

“We don’t really know what chronic effects may be accumulating in this population,” says Joel Peterson in this video about the West Van Buren site, where groundwater filtration wells sit in the middle of the community, by the highway and across from a graveyard. “We are definitely concerned that no one is paying attention to this.”

Some chronic effects are documented just west of Phoenix, where another site of groundwater contamination lurks: the Maryvale plume. Here, a childhood leukemia cluster was discovered in the late 1980s, when 35 kids died with leukemia in the Valley. Back in 1987, doctors said there was no need to panic. The reality? Kids – newborns to 19-year-olds – died at twice the national rate.

These tragic troubles aren’t over, either. One woman, who has cancer, told the Phoenix New Times that of the dozen houses on her street, ten people have recently been diagnosed with cancer. Four have died.

The plume still lies below the local park, middle school, and residential areas.

It’s only one of 38 on Arizona’s priority list. These sites dot Arizona, including the Motorola 52nd St Site, contaminated with solvents since the 50s. Drums storing waste chemicals were suspected of leaking in the 70s, and in the 80s the company reported that a 5,000-gallon drum had leaked. Trichloroethylene concentrations at the facility hit as high as 1,470,000 parts per billion. Cleanup, treatment, and troubleshooting by Motorola and the state and federal government ensued, and billions of gallons of groundwater have been treated. Cleanup is still underway, over a half-century later.

Underground contamination in Maryvale spreads far beyond the middle school. / Source: Phoenix New Times

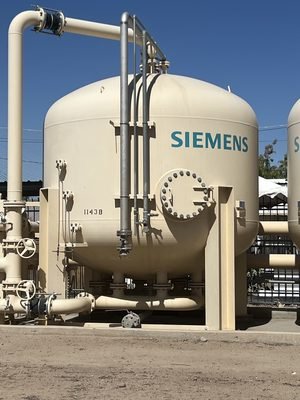

Superfund sites in Arizona span across the state, denoted by the red pentagon. / Source: Arizona Department of Environmental Quality

Across the country, small steps forward are taken. Hundreds of miles away in Camp Lejeune, N.C., years of pressure are finally yielding momentum: The Camp Lejeune Justice Act is expected to pass the Senate this week, allowing veterans exposed to its contaminated water to file claims. Reports say that Maryvale will be under the microscope again, with a new cancer cluster study expected to be complete in a few years – decades after the first study, most state researchers now believe the 1980s cluster is a "true cluster."

How many more are there?

~ Maryam Zafar, Sam Lettenberger & Ray Dorsey, MD

“POLLUTED AIR”

The health we have today may reflect our environment from decades earlier. This may be especially true for Parkinson’s disease. The lag between exposure to the environmental toxin trichloroethylene (TCE) and the development of Parkinson’s is 10 to 40 years. For pesticides, it may be similar. The same might also be true for air pollution.

The adverse health effects of outdoor air pollution are great and growing. The Global Burden of Disease study estimates that the toxic smog that plagued Los Angeles in the 1970s and clouds in Beijing today are responsible for 7 million deaths per year, equal to the number who have died worldwide from the current COVID-19 pandemic. Air pollution reduces life expectancy for all of us by three years. And these numbers do not include the likely effects of air pollution on brain diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

In the early 1990s, Mexico City had the most polluted air in the world. A young, creative physician, Dr. Lilian Calderón-Garcidueñas, sought to determine its effects. She did so in an unorthodox way. She looked at the brains of young children who died in car accidents. What she found was disturbing. In the brains of infants as young as 11 months old, she found the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, a misfolded amyloid protein. She also found the signatures of Parkinson’s disease in the brains of young children.

Research since that time has increasingly linked air pollution to Alzheimer’s and to Parkinson’s. The risk for the former may be great, and for the latter more modest, but nonetheless concerning. For example, Dr. Beate Ritz at UCLA and her colleagues found that individuals who were exposed to air pollution from traffic-related sources in Denmark had an increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

Suspended in the clouds of smog that we see on especially polluted days are pieces of dirt and soot. When we breathe in these particles, we either sneeze or cough most of them out. However, some of this “particulate matter” are very small, twenty times smaller than the width of our hair. These small particles may bypass our nose’s normal protective mechanisms, travel into the nerves that are responsible for smell, and gain direct entry into our brain. Hitchhiking on these particles are toxic metals including platinum from catalytic converters, iron from brakes, and lead from leaded gasoline.

Great Smog of 1952

Before air pollution made its way to the United States, India, and China, it began in the United Kingdom. When Dr. James Parkinson wrote his classic essay on six people with the disease in 1817, he did so among the London Fog. As recalled in the television series, The Crown, the London Fog had little to do with weather and everything to do with air pollution. In the Great Smog of 1952, visibility was reduced to three feet and up to 12,000 people died from its acute effects. Today, its chronic effects may still be felt among seniors who were young children 70 years ago.

Today, the air on the streets of England is less polluted. The air quality index for Oxford during my visit was in the “good” range. However, walking on the streets of Oxford, which are in close proximity to cars and buses, I likely saw more older individuals with Parkinson’s than Dr. Parkinson did two centuries earlier in London. It made me wonder why.

Oxford is not a rural area with high pesticide use, nor are all the individuals I saw likely to have had significant exposure to TCE or be carriers of genetic mutations linked to Parkinson’s. Had these seniors been breathing in toxic air for decades? Did this begin when they were babies in trams or strollers when their noses would have been closer to automobiles’ tail pipes? Is lead, which is still present in the British air 23 years after leaded gasoline was banned, part of the blame? Are other metals or components of air pollution?

Air pollution may also be hazardous for those who already have the disease. A recent study found that among those with Parkinson’s, rates of hospitalizations increased when the air quality dipped. More robust studies link polluted air to faster rates of cognitive decline among older adults in Los Angeles. Some of this may be preventable through air filters at home, closed circulation of air when driving, and avoiding heavily polluted areas. Despite the risks and concerns, investigation of the role of air pollution in Parkinson’s disease has been remarkably limited. Of the 100,000+ papers published on Parkinson’s since 2000, only 127 address air pollution.

Roger Bannister breaking the four-minute mile barrier

Not all I saw in Oxford was dark or disturbing. I visited the very modest track where Roger Bannister was the first person to run a mile in under four minutes. The mark was considered to not be possible by some contemporary scientists. However, after completing morning rounds in a London hospital in 1954, the 25-year-old medical student broke the mark on an overcast afternoon on a cinder track, passing the finish line in a time of three minutes and 59.4 seconds. Six months later, he would retire as the world’s fastest man to pursue a distinguished career in neurology. After devoting decades to caring for individuals with brain diseases, including Parkinson’s, Sir Roger Bannister died from that same disease in 2018.

I also met the distinguished Dr. Michele Hu, a Professor of Clinical Neuroscience and Consultant Neurologist at the University of Oxford. Dr. Hu not only cares for hundreds of individuals with Parkinson’s, but she and her team also evaluate the earliest features of the disease and develop objective measures of the condition from ubiquitous smartphones. This latter approach was pioneered by a brilliant mathematician, Oxford resident, and wonderful colleague, Dr. Max Little. In 2009, two years after the first smartphone was released, he demonstrated that sophisticated mathematical analysis of voice recordings can differentiate those with Parkinson’s from those without.

Photo of Martin Cowell, Ray Dorsey, Paul Mayhew-Archer, Rob Hayward, and Jack

Finally, the highlight was a visit to the sunlit home of Martin Cowell. There I met the former publisher and his comedian friend Paul Mayhew-Archer along with Rob Hayward and friend Jack, two talented filmmakers. Rob and Jack are producing a documentary of Guy Deacon, a former British colonel, who is traveling through 14 countries in Africa to increase awareness of Parkinson’s and decrease its stigma.

Omotola Thomas, the founder of Parkinson’s Africa who joined us by Zoom, is making it her life’s work to show that people with Parkinson’s across the continent – like those everywhere – need compassion and care, not blame. While rates of Parkinson’s disease in sub-Saharan Africa are currently among the lowest in the world, the use of pesticides and air pollution are both rising. Combined with increasing longevity, this could create yet another large wave of the expanding Parkinson’s pandemic. A preview of their moving documentary has been released and is available here.

The first step to ending Parkinson’s or any disease is to determine its cause or causes. Identifying the causes of diseases enables them to be cured or even better – prevented. This was true of cholera, scrotal cancer, and lung cancer, all of which had their causes first identified in England. Bacteria polluting the drinking water caused deadly outbreaks of cholera and killed tens of millions. Having young boys clean chimneys in the 18th century led them to develop cancer of their scrotums, and smoking causes lung cancer. Once the causes were identified, clean water, child labor laws, and smoking warnings, taxes, and restrictions soon followed. The result? Fewer cholera outbreaks, the near disappearance of scrotal cancer, and falling rates of lung cancer.

The COVID pandemic showed us how quickly air pollution, a likely contributor to Parkinson’s, can be addressed. In the span of eight months, brown skies turned blue around the world.

If we keep skies blue, future visitors to Oxford may rarely see individuals with stooped postures and shuffling gaits. Fewer of us will develop dementia, and subsequent generations will live longer, healthier lives.

— Ray Dorsey, MD

“CLOUDY THINKING?”

From England, I flew to Madrid to attend the International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. There I saw countless friends and colleagues, many of whom I had not seen in years. I also witnessed how little has changed in our approach to the disease.

Despite the fact that most of Parkinson’s is due to environmental factors, the topic is almost entirely ignored. The program for the Congress had a plenary session devoted to how genetics will impact clinical care and 67 abstracts on the genetics of Parkinson’s. By contrast, no sessions were devoted to environmental causes, and only 32 abstracts were focused on “epidemiology.” Genetics are important and may explain why some farmers, for example, exposed to pesticides develop Parkinson’s and why some do not. Yet, we have known for over a century that only ~15% of people with the condition have a family history of the disease. The environmental causes need more of our attention.

Similarly, the Congress had a large focus on treatment including a clinical trial update, a discussion on choosing the best therapeutic targets, a video session on “fresh chemodenervation strategies” for treating symptoms, and numerous others on physical, speech, and surgical therapies for the disease. Again, all are important, but so is prevention, which did not appear even once in the program.

The status quo is clearly not working:

Parkinson’s is the world’s fastest growing brain disease

Almost no organization is primarily focused on preventing the disease

Over the last five years, use of the pesticide paraquat, banned in China, has doubled in the U.S.

In wealthy nations, a large portion of affected individuals do not receive specialty care

In less wealthy nations, the majority lack access to a safe, inexpensive, highly effective treatment (levodopa)

The U.S. government spends 100 times more on Parkinson’s care than on Parkinson’s research

We have had no therapeutic breakthroughs for Parkinson’s this century

Reflection and a call for change might be in order, but I saw or heard neither.

Unfortunately, change is not likely to come from within the profession. It must come from the outside, from those who see the world differently. Spain still has a constitutional monarchy, but its rule is derived from its people. Until the millions affected by Parkinson’s disease demand change, the status quo will reign supreme.

— Ray Dorsey, MD

The Prescription for Action: the newsletter

Prescription for Action is an email newsletter for the Parkinson’s community curated by the Ending PD team.

Each issue covers the latest developments in the prevention, advocacy, care, and treatment of Parkinson’s disease.